The debate around "inversions"—the process of American companies buying foreign companies to access capital and lower tax rates overseas—has reached the dinner table.

But while the debate escalates over the dozen or so companies that are pursuing this endlessly wonky and complicated legal loophole, there are dozens more loopholes that companies are jumping through here at home, that end up forfeiting hundreds of billions of dollars in revenues.

Consider "bonus depreciation."

When a consumer purchases a new car, the value depreciates as soon as he or she drives it off the lot. Imagine if one could write off up to half the value of that car immediately, given that it would—eventually—depreciate.

That's what this tax credit has done for capital-intensive companies like those in the industrials and utilities space. Enacted in the early 2000s as part of the Bush-era tax cuts, bonus depreciation was meant to spur capital spending—especially in small businesses—and was extended in 2010 as a then-fragile economy continued to heal.

"Without bonus depreciation, we hold and use equipment longer," said small-business owner Dan Fesler, CEO of Minneapolis-based Lampert Lumber, to a House of Representatives committee in 2010. "We often consciously make the decision not to purchase equipment if it is not affordable to us."

Read MoreTaxreform: You don't care, and neither does DC

But what spurred small businesses like Fesler's to buy hundreds of thousands of new computers and trucks has become quite costly, as large-cap companies take advantage of it, too.

Waste Management confirmed to CNBC it was paying up to $80 million more in income taxes this year, with bonus depreciation having expired at the end of the year. (The Wall Street Journal had reported the company previously recorded some $1 billion in these tax credits since inception.)

Perhaps the most egregious users of bonus depreciation are the utility companies, many of which have a negative tax rate because of how much they write off.

A June study by Citizens for Tax Justice and the U.S. Public Interest Research Group found that Pepco Holdings, Pacific Gas and Electric, Wisconsin Energy and American Electric Power saw their effective tax rates go negative from 2008 to 2012, largely due to bonus depreciation.

Power companies have said it helps them pass lower rates on to customers, but there's no evidence that's the case—and no evidence, really, at all that the policy has been effective.

In fact the Congressional Research Service (a nonpartisan policy research arm that prepares reports informing members of Congress of the effects of certain legislation), wrote last month that the credit's "temporary nature is critical to its effectiveness." And that even considering that, "research suggests (it) was not very effective."

Read More

Currently, bonus depreciation is in the crosshairs of Congress, as the House voted in July to modify and extend it, even though it would add roughly $233 billion to the deficit over the next five years and $287 billion over the next 10 years, according to House estimates.

As it awaits the Senate, some companies, like Texas-based Waste Connections, are said to be holding off on decisions over increasing capital spending, citing the uncertainty around future tax benefits.

That uncertainty grew when the White House weighed in last month, saying, "This provision was enacted in 2009 to provide short-term stimulus to the economy, and it was never intended to be a permanent corporate giveaway." If the president were presented with a bill asking to extend bonus depreciation "without offsets," the statement read, "senior advisors would recommend he veto the bill."

On the other hand, Washington has been quite favorable toward another creative tax credit that companies from Campbell Soup to Verizon have been taking advantage of since the late 1980s: Credits for building affordable housing.

Banks and insurers have long been required by law to reinvest near their depositors, per the Community Reinvestment Act. Many have done so through low-income housing tax credits (LIHTCs, pronounced "lie-techs"), that allow them to fund construction of multifamily housing with credits that sell for less than 100 cents on the dollar.

The company then gets to write off the full amount of its financing over 10 years, earning a return on its investment.

Read MoreEnd this corporate tax handout now: R&D incentives

Since the 1990s, the program has been responsible for 40,000 new affordable housing developments, at a cost of roughly $92 billion, according to estimates from the Joint Committee on Taxation.

The cost for the average LIHTC has climbed from 67 cents per dollar of tax credits in 2009 to 93 cents—even with the rise in cost, the investment still represents a lucrative opportunity for yield in a low-interest rate environment. That's why Fred Copeman, partner in CohnReznick, says nonfinancial companies have begun to build.

"The housing credit program is the last legitimate tax shelter," Copeman told CNBC. Companies can bring down their overall tax rate and "increase after-tax earnings in a way that involves a program favored by Congress."

And residents, who benefit from lower rents, may never know that grocer Kroger, or paint company Sherwin-Williams are the backers of their building.

"At most, you might see a sign that says, 'Construction financing provided by XYZ bank,'" Copeman said.

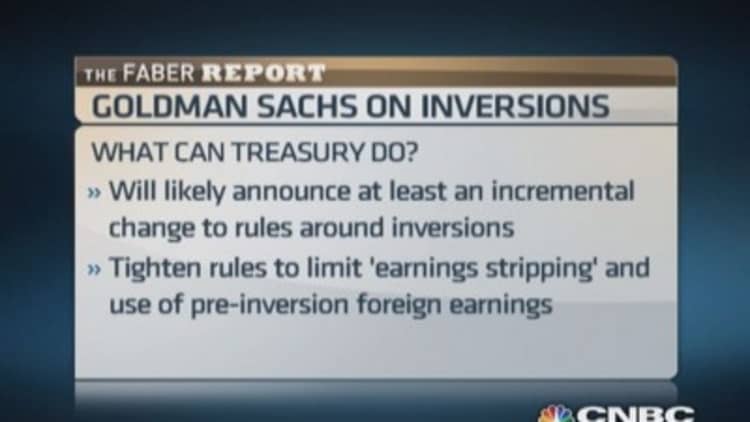

Read MoreObama aims to move fast to curb inversions

So it's unlikely residents of a 240-unit apartment complex in Allston, Massachusetts, know that tech giant Google put up $28 million for their development.

Google has been among the most active in the LIHTC space, deploying hundreds of millions of dollars since the financial crisis to fund developments in Iowa, Wisconsin and its home state of California. A Google spokesman would not confirm the extent of the company's investment, but did confirm that the money is deployed via its treasury department and seeks what he called "a healthy return."

The technology company now relies on private equity firm Red Stone, a third-party syndicator, which matches corporations to developments seeking tax-friendly financing. Google has branched out of its core interest in equity, beginning to buy some $30 million in bonds associated with a San Antonio apartment complex.

Red Stone executive Ryan Sfreddo says companies like Google are ultimately seeking good investments, but get the added benefit of providing a social good.

That's caused demand from companies like Google and others to soar. Currently, Sfreddo said, "There's at least $3 of applications for every dollar of available credit in a given state; there is also an imbalance in the capital markets today in that there is significantly more capital seeking LIHTC investments than there are available LIHTC deals."

While banks and insurers still make up some 80 percent of the market, nonfinancial companies like Verizon, Kroger, Sherwin-Williams and UnitedHealth Group have jumped in, too.

But it's not a given. Ultimately, it's up to states and state-backed developers to choose who gets them.

Each state, by federal law, gets $2.25 per capita to award in low-income housing tax credits. Currently, Sfreddo said, "there's at least $3 of (corporate) applications for every dollar of credit in a state."

Read MoreWhite House loosens restrictions on lobbyists

The amount of spending on LIHTCs has increased to $11.5 billion estimated for 2014, from $4.5 billion in 2009, according to Joe Hagan, president and CEO of the National Equity Fund.

And the amount of state spending may get upped by Congress, too: These credits were one of only two to survive a recent attempt at a tax reform bill put forth by Rep. Dave Camp, R-Mich., and Copeman said he sees support from both parties for the credit going forward.

A tale of two tax loopholes—but two very different stories.

—By CNBC's Kayla Tausche